Parts of a Pig: The Ultimate Guide to Pork Done Right

Disclosure: This post contains affiliate links. If you buy through these links, I may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. You can read the full disclosure for more information. It helps keep this site running — thank you for your support!

When most people think of a pig, the first thing that comes to mind is probably bacon sizzling in a pan.

Fair enough—bacon deserves the spotlight. But there’s so much more to a pig’s offerings than breakfast strips.

From the shoulder to the belly, from the ham to the jowl, this animal has been feeding humans for centuries, and almost every part can be eaten if you know what you’re doing.

But do you know the difference between pork butt and pork shoulder? Or why pork belly has become a superstar cut on restaurant menus?

Ever wondered what makes a ham hock so different from the ham itself—or where on the pig spare ribs actually come from?

By the end of this guide, you’ll know every cut, how it’s used, and why nose-to-tail eating just makes sense.

TL;DR: Parts of a Pig

- A pig is divided into primal cuts: shoulder, loin, belly, and leg — each broken down into retail cuts like pork shoulder, pork loin, pork belly, and ham.

- Tender cuts like pork loin and tenderloin suit high-heat cooking, while tougher cuts such as pork butt, picnic ham, and ham hock shine with roasting, smoking, or braising.

- Specialty parts — jowl, snout, ears, trotters, tail, and head cheese — show why nose-to-tail eating makes sense and deliver flavors modern diets often forget.

- The best pork comes from pigs raised on natural diets, producing richer, fattier, and more nourishing meat. Heritage breeds add even more depth and quality.

The Big Picture: Primal Cuts of a Pig

Before we dive into pork belly, ham hock, and all the tasty details, it helps to understand how a pig is divided up.

Butchers don’t just hack away randomly—they work from what’s called the primal cuts. These are the big sections of the animal, and from them we get all the smaller retail cuts you’ll see on store shelves.

A pig is usually divided into four main primal areas: the shoulder, the loin, the belly (sometimes called the side), and the leg.

The head, feet, and other parts are also used, though they often get less attention outside of traditional cooking. From these primal areas come familiar favorites like pork shoulder for pulled pork, pork loin for chops, and spare ribs for BBQ.

Think of primal cuts as the butcher’s blueprint. Once you know the map, the rest of the pig makes a lot more sense.

Shoulder Region: The Workhorse of the Pig

If you’re looking for meat that works hard, look no further than the pig’s shoulder. This area carries a lot of muscle and connective tissue, which makes it one of the tougher cuts at first glance.

But don’t be fooled—when cooked right, the shoulder transforms into some of the most flavorful pork you’ll ever eat.

Pork Shoulder & Pork Butt

Here’s where it gets a little confusing. Pork shoulder and pork butt actually come from the same front section of the pig, just different areas.

The pork butt (also called the Boston butt) sits higher on the shoulder blade, while pork shoulder comes from the lower part of the front shoulder.

Both are marbled with fat and benefit from slow cooking methods like roasting, braising, or smoking. That’s why they’re the go-to choice for pulled pork.

Picnic Ham

Move a bit lower on the front leg, and you’ll find the picnic ham. Despite its name, it’s not the same as the traditional ham from the rear leg.

The picnic ham is a shoulder cut, often sold bone-in, and is usually smoked or cured. It’s slightly less tender than a true ham but is budget-friendly and delicious when prepared low and slow.

The Loin & Back: The Tender Zone

If the shoulder is the workhorse, the loin is the luxury suite. Running along the pig’s back, from the shoulder down to the rear leg, this section doesn’t get as much exercise. Less work means less connective tissue and more naturally tender meat. That’s why so many desirable cuts come from here.

Pork Loin

The pork loin is a long, lean strip of meat running along the backbone. It’s versatile and can be roasted whole, cut into chops, or sliced into boneless steaks.

Cook it with a gentle touch—too much high heat and it dries out quickly.

Tenderloin

Tucked just beneath the loin is the tenderloin, one of the most tender cuts of the pig. It’s smaller and leaner and prized for quick cooking methods like grilling or pan-searing.

Back Ribs & Baby Back Ribs

Attached to the top of the loin are the back ribs, often called baby back ribs. These are shorter and leaner than spare ribs from the belly.

When prepared properly—usually smoked or slow roasted—they deliver a balance of tenderness and flavor that barbecue fans swear by.

Belly & Side: Fat, Flavor, and Bacon

If the loin is prized for tenderness, the belly is worshipped for flavor. Sitting along the lower part of the pig, this section is rich, fatty, and downright irresistible when prepared the right way.

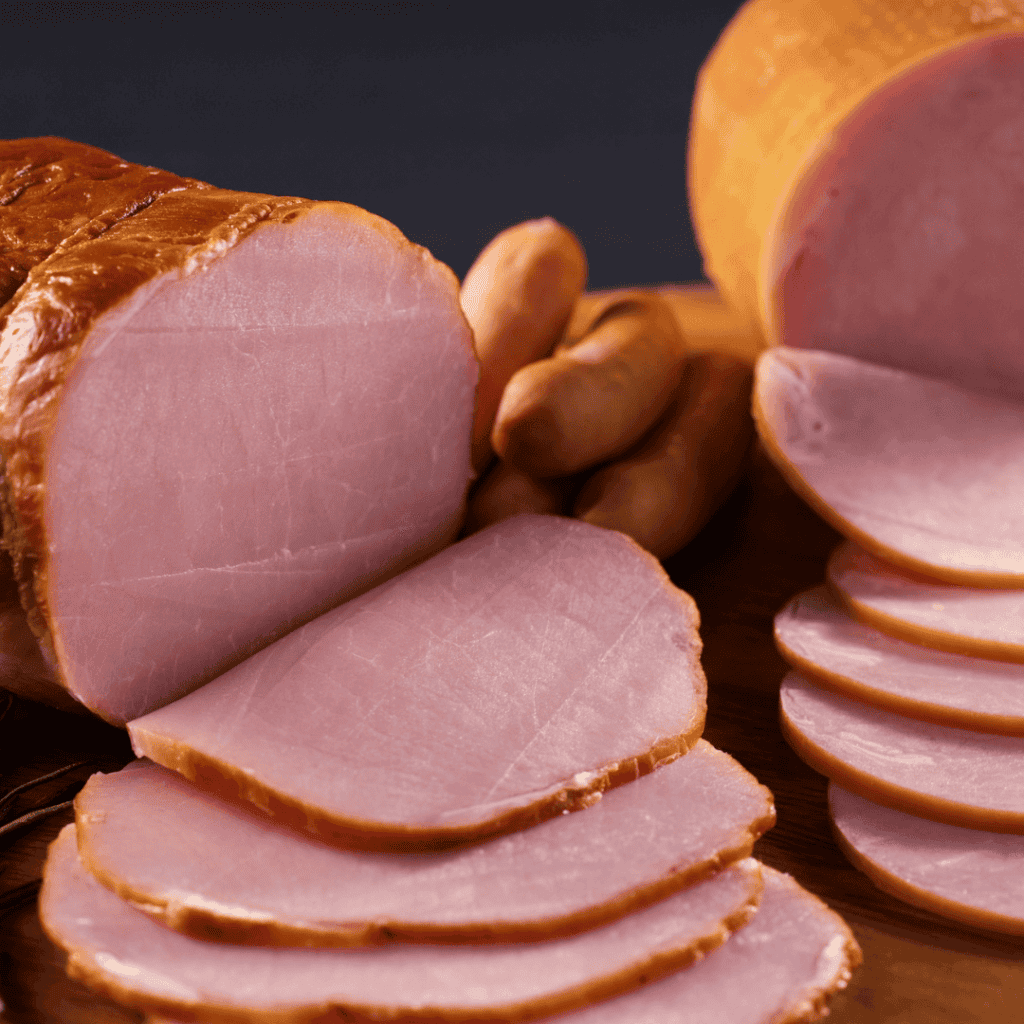

Pork Belly

This is the star of the show. Pork belly is where we get bacon—cured, smoked, and fried into those crispy strips everyone loves. But pork belly isn’t just about breakfast.

Fresh, uncured belly can be roasted or braised, producing juicy layers of fat and meat that melt in your mouth.

In many cuisines, it’s rolled, seasoned, and slow-cooked to create dishes that balance richness with a crispy finish.

Spare Ribs

Just below the loin and running along the belly, you’ll find spare ribs. Larger and meatier than baby back ribs, they’re a barbecue staple.

Spare ribs have more connective tissue, so they benefit from low, slow cooking or smoking until they’re fall-off-the-bone tender.

Bacon & Fatback

While pork belly gives us bacon, the back also provides fatback—a thick layer of fat often used in sausages, cured meats, or even rendered for cooking fat.

Together, these parts make the pig one of the most generous animals when it comes to flavor.

Specialty & Less Common Parts

Beyond the familiar pork belly, shoulder, and ham, the pig offers a wide range of other parts that many overlook.

In traditional cooking—and especially in nose-to-tail eating—nothing goes to waste. These cuts may not be on your supermarket’s front board, but they’ve fed humans for centuries.

Jowl (Cheeks)

The jowl, or cheek, is a fatty cut that can be cured into a type of bacon or turned into guanciale, the Italian specialty. When prepared, it’s rich and smoky and adds depth to stews or sausages.

Ears

Pig’s ears are full of cartilage and connective tissue. When braised, they become tender; when fried, they turn crispy. They’re popular in Asian cuisines, often sliced thin into salads or stir-fries, and even served grilled at street markets.

Snout

The snout isn’t just decorative—it can be braised or simmered until gelatinous, adding body to soups and stocks. It carries a meaty, chewy texture that some cultures prize for flavor and richness.

Tail

Often forgotten, the tail is loaded with connective tissue, fat, and bones. When braised or smoked, pig tails release incredible flavor and help thicken stews or soups.

In the American South, they’ve long been used in slow-cooked beans and collard greens.

Trotters (Feet)

Pig’s feet are a collagen powerhouse. Slow cooking releases gelatin from the bones and connective tissue – a chef’s secret to turning broths and sauces silky.

Trotters are also baked, braised, or deep-fried in different cuisines.

Skin & Cracklings

Pork skin is versatile. It can be left on belly or shoulder cuts for extra crunch, or cooked separately into pork rinds (cracklings). These are fatty snacks but rich in protein and minerals from the skin.

There’s something of a knack to getting the perfect crackling, at least for me. Sometimes I get it bang on and sometimes not. If you know the secret, please let me know in the comments.

Fatback

This solid layer of fat from the pig’s back is used to enrich sausages, render into lard, or add moisture to leaner cuts. Old-school butchery never wasted it.

Organs (Offal)

Nose-to-tail eating wouldn’t be complete without organs. Pig liver, heart, kidneys, lungs, stomach, and even the spleen are edible. Each delivers different nutrients and flavors, with liver being one of the most nutrient-dense foods available.

Head Cheese (Brawn)

Not a cheese, but a terrine-like dish made from the simmered head (including cheeks, tongue, sometimes ears). The collagen sets into a meat jelly that’s sliced cold. A true nose-to-tail tradition.

I once made head cheese from a whole pig’s head following Fergus Henderson’s recipe. Honestly, it’s one of the best things I’ve ever tasted. Give it a go if you feel the urge and let me know your thoughts.

Blood (Black Pudding)

Pig’s blood is often used to make blood sausages, such as black pudding in the U.K. or morcilla in Spain. It’s mixed with fat, oats or rice, and spices, then cooked into a savory, nutrient-rich food.

Black pudding is well known where I’m from in the UK as part of a full English breakfast. That said, there is a divide; some love it and some hate it, with little opinion in between.

I’m a fan—it tastes amazing, and I reckon the reason others don’t like it is more to do with the fact that it’s blood than the taste.

How Muscle, Connective Tissue & Fat Influence Cooking

Not all pork is created equal. Some cuts are naturally tender, while others feel tough until you treat them with patience.

The difference comes down to how much the pig used that part of its body and what it’s made of—muscle, connective tissue, or fat.

Muscle Workload Matters

The more a muscle works, the tougher it tends to be. The shoulder and leg are prime examples—both are packed with flavor but need longer cooking times to break down the fibers.

Cuts like pork loin or tenderloin, on the other hand, come from muscles that do less work. This is why they’re naturally tender cuts and better suited to high-heat methods like grilling or frying.

Connective Tissue: Tough Turned Tender

Connective tissue makes certain cuts feel stringy or chewy at first—think pork shoulder, ham hock, or spare ribs.

However, given time, moisture, and gentle heat, that tissue melts into gelatin. This transformation is why braising tougher cuts results in meat that falls apart and sauces that taste rich and silky.

The Role of Fat

Fat is flavor. Pork belly, jowl, and fatback are fatty cuts, and they’re loved precisely because of the richness they add. That fat bastes the meat as it cooks, keeping it juicy and adding depth.

Leaner cuts like pork loin or tenderloin often need help—whether brined, wrapped in bacon, or cooked carefully to avoid drying out.

Bones Bring Flavor Too

Don’t overlook the bones. Cuts like back ribs, spare ribs, and trotters rely on bones to add flavor and body.

Slow cooking with bones enriches soups, stews, and sauces with minerals and a deeper taste that boneless cuts just can’t match.

Retail Cuts & Butcher Terms You’ll See

Once the pig is divided into primal cuts, it’s broken down further into what butchers call retail cuts. These are the pieces we actually buy—chops, roasts, ribs, and steaks.

If you’ve ever stood at the meat counter confused by labels, you’re not alone. Different regions (and even different butchers) sometimes use different names for the same thing.

Bone-In vs Boneless

Bone-in cuts often cook up juicier because the bones help retain heat and moisture. Think bone-in pork chops or a bone-in picnic ham.

Boneless cuts, like a pork loin roast or pork butt roast, are easier to carve and prepare quickly, but they can lose some flavor along the way.

Rolled & Tied

Large cuts such as pork belly or shoulder are sometimes rolled, tied, and roasted. Rolling evens out the shape, making them cook more evenly and helping lock in fillings or seasonings.

Steaks, Roasts & Chops

You’ll often see pork steaks and chops from the loin and tenderloin—smaller cuts for quick grilling or frying. The shoulder, leg, and belly are more often sold as roasts for longer, slower cooking.

Prepared & Cured Options

Beyond fresh pork, you’ll also see cured and prepared options: smoked hams, brined picnic hams, sausages, bacon, or even head cheese.

These give variety and convenience but are all rooted in the same primal cuts.

Knowing the butcher’s lingo helps you buy the right cut for the right cooking method and avoid the classic mistake of trying to grill a cut that really needs braising.

From Pig to Plate: Cooking Tips by Cut

Once you know the parts of a pig, the next step is cooking them right. Each cut has its own personality; the best results come when you match the method to the meat.

High Heat for Tender Cuts

Cuts like pork loin, tenderloin, and pork chops are naturally tender. They shine with high-heat methods, such as grilling, frying, or quick roasting.

Keep an eye on them, though. Overcooking makes them dry fast. A good rule is to cook just until done, then rest the meat before slicing.

Low and Slow for Tougher Cuts

Shoulder, picnic ham, pork butt, and ham hock are tougher cuts with plenty of connective tissue. These respond beautifully to braising, smoking, or slow roasting.

Long cooking times at gentle heat turn them from chewy to melt-in-your-mouth tender.

Balancing Fatty Cuts

Pork belly, jowl, spare ribs, and fatback are fatty cuts. They deliver incredible flavor but need the right handling.

Roasting or grilling renders the fat, leaving crispy edges with juicy centers. Bacon, of course, shows what happens when belly meat is cured, smoked, and fried just right.

Bones Build Flavor

Back ribs, spare ribs, shanks, and trotters are best when cooked slowly. The bones release minerals and collagen, enriching sauces and soups.

That’s why bone-in roasts or ribs often taste better than their boneless counterparts.

Prepared Classics

Let’s not forget prepared pork: smoked ham, brined picnic cuts, sausages, and head cheese.

These showcase traditional preservation methods and prove that pork has been central to human food culture for centuries.

How to Source the Best Pork (Diet, Farming & Quality Matters)

Not all pork is created equal. The quality of pork belly, pork shoulder, or ham hock doesn’t just come from the butcher’s knife—it begins with how the pig was raised and what it ate.

What the Pig Ate

A pig’s diet directly shapes the flavor, fat quality, and tenderness of its meat. Pigs fed a natural, varied diet produce firmer fat and richer flavor, while those raised on industrial feed often yield leaner but less tasty pork.

How the Pig Lived

Pigs that roam freely, root in the soil, and forage develop stronger muscles and healthier fat compared to those confined indoors. Stress-free handling also makes a big difference—calm pigs mean better meat.

Breed & Farming Practices

Heritage breeds often carry more marbling, while modern commercial pigs are bred for speed and leanness. Look for labels like “pasture-raised,” “organic,” or “heritage breed” when you can, and don’t be afraid to ask your butcher where the pork came from.

Breed Makes a Difference Too

Not all pigs are built the same. Heritage breeds like Berkshire, Tamworth, or Mangalitsa are prized for their marbling, flavor, and rich fat, while modern commercial breeds are typically leaner and bred to grow quickly.

Choosing heritage pork is often worth the investment if you want beautifully crisp pork belly or ham with a deeper flavor.

The Takeaway

The best pork comes from pigs that live and eat as close to their natural environment as possible. This isn’t just better for the pig’s quality of life—it produces meat that’s richer, tastier, and more nourishing for us too.

Summary & Takeaway

The pig is one of the most generous and delicious animals we eat. From pork belly and spare ribs to ham hock, pork shoulder, and even the jowl, almost every part can be cooked, cured, or prepared into something delicious.

Some cuts are naturally tender, others need slow cooking to unlock their flavor, but together they form a full picture of why pork has been a cornerstone of human food for centuries.

If there’s one thing to remember, it’s this: the best eating comes from respecting the whole animal. That means knowing your cuts, cooking them the right way, and sourcing pork from pigs raised on a natural diet in good conditions. It’s better for the pig, better for the meat, and better for us.

So next time you’re at the butcher, don’t just reach for the bacon. Explore other parts of a pig, cook them well, and taste why nose-to-tail eating makes perfect sense.

Eating pork is part of the animal-based, carnivore, ancestral, or what I call the Ultimate Human diet. It is not only tasty but extremely healthy, providing your body with the fuel it craves.

And that’s it… have a nutritious day!

FAQs

What are the parts of a pig called?

The parts of a pig are divided into primal and retail cuts, including pork shoulder, pork loin, pork belly, ham, ribs, and specialty areas like jowl and ham hock.

What are the parts of the body of a pig?

The body of a pig is divided into shoulder, loin, belly, and leg. Other parts include the head, ears, snout, trotters, and internal organs, all prepared differently across cuisines.

What is a whole pig leg called?

A whole pig leg is called a ham. Fresh, smoked, or cured, this cut is a centerpiece roast, with the lower part known as the ham hock or shank.

What are pig innards called?

Pig innards are called offal. This includes liver, kidneys, heart, lungs, and stomach. These cuts, while less popular today, are nutrient-rich and form a vital part of nose-to-tail eating.